How Your Eyes Quietly Influence Fatigue, Focus and Anxiety

Most people think of vision as something practical. Can you see the road? Read a screen? Recognise a face across the room?

What’s rarely discussed is what happens behind the eyes, in the brain! When vision isn’t quite right.

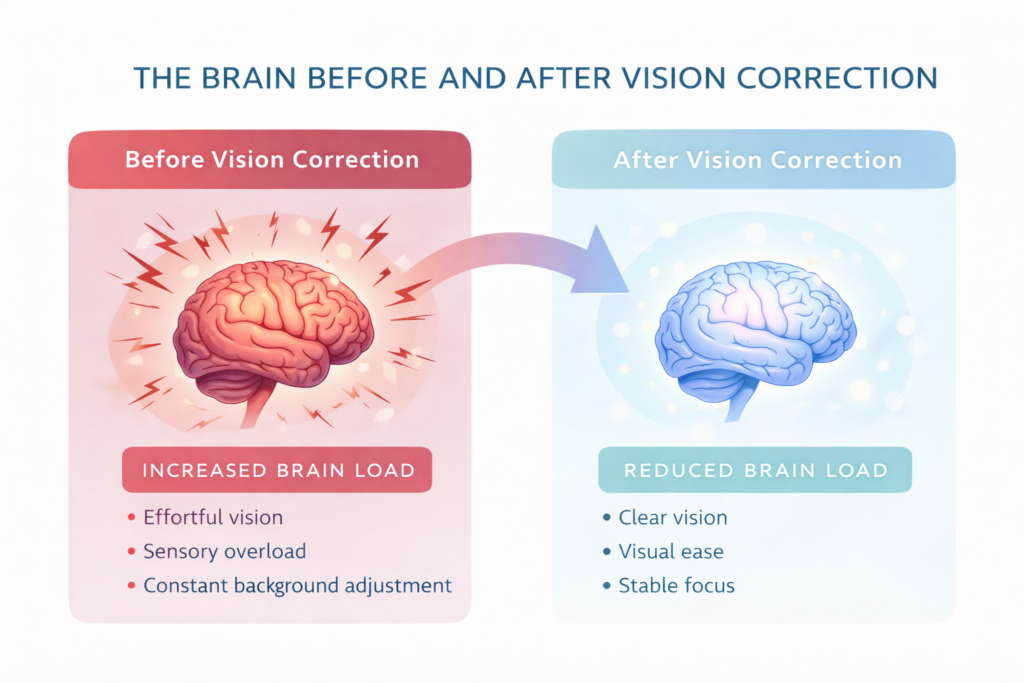

Long before someone realises their eyesight has changed, the brain often steps in to compensate. It sharpens, guesses, fills gaps, and works harder to interpret the world. That effort is usually invisible, but over time it can quietly affect how tired, tense, or mentally overloaded a person feels.

This relationship between the eyes and the brain is sometimes described as a loop. When vision is compromised, even subtly, the brain increases effort. Increased effort leads to fatigue, reduced focus, and heightened sensitivity. Those symptoms are then often blamed on stress, screens, or ageing when vision may be playing a much larger role than expected.

Vision Is Not Passive Information

Vision is not a simple camera feed. It is an active neurological process.

Roughly a third of the brain is involved in visual processing. Signals from the eyes are constantly being interpreted, corrected, stabilised, and prioritised by the visual cortex. When clarity is good, this happens efficiently and quietly. When clarity is reduced through blur, strain, dryness, or inconsistent focus; the brain does more work to achieve the same result.

This extra effort is rarely felt as “eye strain” alone. More often, it shows up as:

- Mental tiredness that builds through the day

- Difficulty concentrating for long periods

- Irritability or low-level tension

- Feeling visually overwhelmed in busy environments.

Because these symptoms feel cognitive rather than visual, vision is often overlooked as a contributing factor.

The Hidden Cost of Visual Compensation

When the eyes are not delivering clean, stable information, the brain compensates in subtle ways.

Constant Focus Correction

Why your eyes never quite relax

When vision isn’t perfectly clear, the brain continuously fine-tunes focus in the background. These micro-adjustments happen without conscious effort, but over hours of screen use or reading, they quietly drain mental energy. It’s why some people feel tired after visually demanding days, even without obvious eye strain.

Enhanced Edge & Contrast Processing

When the brain sharpens what the eyes can’t

If contrast or sharpness is reduced, the brain works harder to define edges and outlines. Text, faces, and moving objects require more interpretation, particularly in low light or on screens. This extra processing can create a sense of visual pressure or tension, especially in busy environments.

Increased Depth & Motion Resolution

Why movement and busy scenes feel overwhelming

When visual input is inconsistent, the brain spends more time resolving depth, movement, and spatial relationships. Crowds, traffic, or scrolling screens demand more attention, which can lead to sensory overload or the feeling of being visually “on edge”, even when eyesight seems acceptable.

This constant background effort consumes mental energy.

For someone with an active lifestyle, screen-heavy work, or long driving hours, the effect can accumulate quietly. By evening, they may feel exhausted without understanding why. Over weeks or months, that fatigue can start to influence mood, patience, and stress tolerance.

Importantly, this doesn’t require poor eyesight in the traditional sense. Even mild blur, early presbyopia, or visual imbalance between the eyes can be enough to increase cognitive load.

Vision, Anxiety and Sensory Overload

There is also a strong link between visual strain and anxiety-like symptoms.

When vision feels unstable, the brain becomes more alert. It pays closer attention to the environment, scanning for clarity and certainty. In busy or visually complex spaces: supermarkets, traffic, crowds, large screens, this heightened alertness can feel like overstimulation.

People sometimes describe this as:

- Feeling on edge in bright or busy places

- Discomfort with night driving or glare

- Needing frequent breaks from screens

- A sense of mental pressure behind the eyes.

These sensations are often misattributed to anxiety itself, rather than the visual system contributing to it.

Why Many Patients Don’t Notice the Change

One of the most interesting aspects of the vision-brain loop is how adaptable it is.

The brain is excellent at compensating, until it isn’t.

Because changes in vision often happen gradually, the brain adjusts incrementally. There is no clear moment where things suddenly feel “worse”. Instead, people adapt their behaviour without realising it:

- Holding phones slightly further away

- Avoiding night driving

- Increasing screen brightness

- Taking more breaks but still feeling tired.

By the time visual correction is considered, many people have normalised a level of strain that no longer needs to be there.

What Patients Often Say After Vision Correction

One of the most consistent comments clinicians hear after successful vision correction is not simply “I see better”.

It is:

“I feel more relaxed.”

Many patients don’t realise how much low-level tension they were carrying until it’s gone. When the brain no longer has to compensate for visual strain, the nervous system often settles, creating a sense of calm that wasn’t consciously missing before.

“I didn’t realise how much effort I was using.”

Visual effort often becomes normalised over time. After correction, patients are surprised by how little energy everyday tasks now require: reading, driving, screen use; once the brain no longer needs to work overtime to interpret the world.

“My head feels quieter.”

This is how many people describe reduced cognitive load. Clear, stable vision allows the brain to process information efficiently, freeing mental space that had been taken up by constant adjustment, correction, and visual vigilance.

These observations reflect what’s happening neurologically. When visual input becomes clear and stable, the brain no longer needs to compensate. Cognitive load reduces. Visual processing becomes efficient again.

For some people, this translates into better focus. For others, improved energy or reduced irritability. The effect is not dramatic or instant for everyone but it is often noticeable once the brain settles into a new baseline.

A Different Way to Think About Eye Care

Modern eye care is not just about sharp eyesight. It’s about how comfortably the brain can interact with the world.

When vision is working well, the brain has more capacity for thinking, decision-making, creativity, and rest. When vision is compromised, even slightly, the brain pays the price quietly.

Understanding this connection helps explain why eye health can influence far more than just what you see, it can influence how you feel.

| Vision Correction Option | Often Considered When | How It May Help the Brain |

|---|---|---|

|

Laser Eye Surgery (LASIK / LASEK / SMILE) |

Stable prescription, healthy corneas, long-term reliance on glasses or contact lenses. | Reduces constant focus correction and visual guesswork, allowing the brain to process images more efficiently and with less background effort. |

| Implantable Contact Lenses (ICL) | Higher prescriptions, thin corneas, or when laser treatment is not suitable. | Provides sharp, stable visual input without reshaping the cornea, reducing the brain’s need to compensate for blur or visual imbalance. |

| Lens Replacement Surgery | Age-related vision changes, difficulty with near focus, or early lens opacity. | Restores consistent vision at multiple distances, easing cognitive load caused by constant refocusing and visual fatigue. |

| Cataract Surgery | Clouded vision, glare sensitivity, reduced contrast, or night driving difficulties. | Improves contrast and clarity, helping the brain interpret visual information without strain, particularly in low-light or complex environments. |

Where This Leaves You

This isn’t an argument for immediate treatment or intervention. It’s an invitation to notice.

If fatigue, focus issues, or visual discomfort have crept in without a clear explanation, it may be worth considering whether your visual system is doing more work than it should.

Sometimes, improving vision isn’t about changing how the world looks, it’s about changing how much effort your brain needs to experience it.