In 2025, with advanced eye surgery available in Cheltenham, South Wales, and across the UK, it is worth asking whether glasses still represent a benign accessory or whether they reveal a hidden disability, one that modern medicine can now resolve.

It is a question that appears more and more in online searches: “Is wearing glasses a disability?” At first, it sounds like a trick. Most people think of disabilities in terms of mobility, hearing, or chronic illness. Glasses, on the other hand, are so common they feel ordinary. Yet if you pause and consider the dependence, the restrictions, and the impact on quality of life, the question becomes less absurd.

In 2025, with advanced eye surgery available in Cheltenham, South Wales, and across the UK, it is worth asking whether glasses still represent a benign accessory or whether they reveal a hidden disability, one that modern medicine can now resolve.

The Legal Perspective

In the UK, the Equality Act 2010 defines disability as a physical or mental impairment that has a “substantial and long-term adverse effect” on daily life. Poor eyesight can be considered a disability under this law, particularly if it cannot be corrected.

However, if vision can be corrected with glasses or contact lenses, it is usually not classified as a disability in legal terms. A person who is blind without their glasses but functions normally with them is not officially disabled. That is the strict legal boundary.

But law and lived experience do not always align.

The Human Experience of Dependence

When you rely on an external device to perform essential daily tasks; driving, working, recognising faces, navigating streets that reliance is itself a form of limitation. Without glasses or contacts, millions of people are effectively impaired.

Think about:

- Driving without correction: Dangerous and illegal.

- Sports and fitness: Glasses slip, fog, and limit peripheral vision. Contact lenses dry out or fall out mid-game.

- Everyday nuisances: Rain on glasses, masks fogging lenses, searching for lost spectacles on the bedside table.

- Psychological impact: Many people dislike how they look in glasses or feel socially limited by them.

By any practical measure, poor eyesight corrected only by external aids behaves like a disability, one that is socially normalised because it is so widespread.

Why 2025 Feels Different

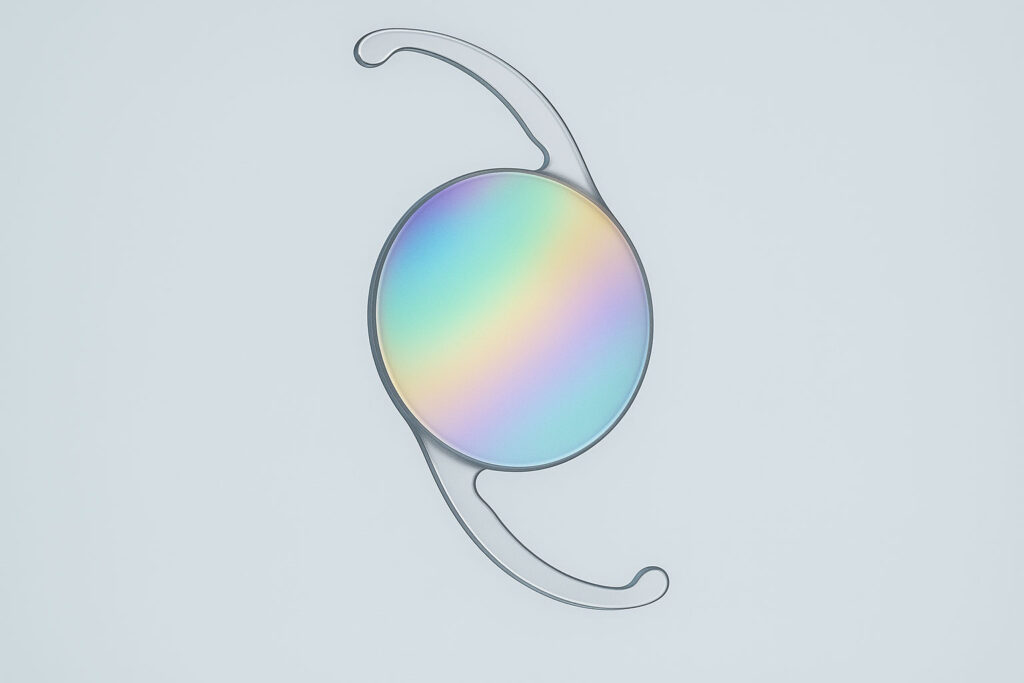

In past generations, glasses were the only option. In 2025, this is no longer true. Laser eye surgery, implantable contact lenses (ICL), and advanced lens exchange procedures provide safe, permanent alternatives.

This shift changes the conversation. If a condition can be corrected permanently, does persisting with temporary fixes count as living with a disability by choice?

It is not unlike mobility aids before joint replacement surgery became standard. Crutches were once a lifelong solution; today, hip or knee replacement often restores independence. Glasses may be entering the same historical category, a transitional solution, not an inevitable one.

Cultural Shifts in How We See Glasses

Glasses have long been associated with intelligence, professionalism, or even fashion. That perception softens their impact. But culture also carries subtle stigmas. In children, glasses can lead to bullying. In adults, they may affect self-image, confidence, and even career opportunities in appearance-sensitive industries.

Contact lenses were once seen as freedom. Now they are increasingly viewed as a compromise high maintenance, prone to causing dry eye, and environmentally wasteful. In fact, discarded contact lenses contribute to microplastic pollution, an issue gaining awareness in 2025.

The truth is, reliance on glasses and contacts has always been a silent limitation. Society just accepted it because alternatives were limited.

Surgery as Liberation, Not Vanity

Eye surgery is sometimes dismissed as cosmetic. This is a misunderstanding. Procedures like SMILE, LASIK, ICL, and cataract lens replacement are functional medicine, restoring an essential sense without external dependence.

- SMILE and LASIK reshape the cornea to correct myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism.

- ICL surgery places a lens inside the eye, ideal for higher prescriptions or thinner corneas.

- Lens exchange removes the ageing lens and replaces it with a clear, advanced implant, correcting presbyopia and cataracts simultaneously.

These procedures do more than sharpen sight. They restore confidence, productivity, and independence. For many patients, the psychological benefit rivals the optical one. It is about waking up and seeing without searching for a device. About running, swimming, or working without limitations.

In this sense, modern surgery removes the features of disability that glasses quietly impose.

The Productivity Argument

From a societal perspective, vision correction improves productivity. Glasses and contacts are a recurring cost; replacements, prescriptions, cleaning solutions. They demand time and management. Surgery is a one-time intervention that frees patients to focus on work, sport, and daily living without interruption.

For employers, there is also a subtle benefit: employees free from visual aids may experience fewer headaches, fewer lost hours due to eye strain, and higher long-term confidence. In regions like Cheltenham and South Wales, where sport, healthcare, and technology industries are strong, the value of unhindered vision is significant.

Reframing Disability in 2025

The word “disability” carries weight, and some bristle at applying it to something as ordinary as glasses. But this is exactly why it matters. When an aid is so normalised we stop questioning it, society underestimates the burden it carries.

In 2025, with advanced surgical solutions available, patients should feel empowered to ask: Do I want to live dependent on glasses, or do I want to be free?

This reframing is not about belittling other disabilities. It is about recognising that poor eyesight has always imposed limitations, ones we no longer have to accept as permanent.

From the Fadi Kherdaji team

So, is wearing glasses a form of disability in 2025? Legally, in most cases, no. But in practice, glasses represent a dependency that shapes how people live, work, and engage with the world.

The difference today is choice. With modern vision correction, from SMILE laser surgery to implantable contact lenses and advanced lens exchange, patients no longer need to accept that dependency.

At Fadi Kherdaji’s clinic, we see this every day. Patients walk in burdened by the subtle weight of glasses or contacts, and walk out weeks later with clear, unaided vision. Their stories remind us that surgery is not vanity. It is liberation from limitation, from dependency, and from a hidden disability society once assumed was normal.

FAQs

1. Is wearing glasses considered a disability in the UK?

Not usually. Under the Equality Act 2010, a disability must cause a substantial and long-term impact on daily life. If vision can be corrected with glasses or contact lenses, it is generally not classed as a disability.

2. Am I disabled if I need glasses to see?

Legally, no. But in practice, needing glasses or contact lenses for essential tasks like driving, working, or recognising faces does represent a dependency, one many patients now choose to eliminate through surgery.

3. Does poor eyesight count as a disability?

If eyesight cannot be corrected, it may qualify as a disability under UK law. However, if glasses, lenses, or surgery can restore functional vision, it typically does not.

4. Can surgery remove the need for glasses?

Yes. Treatments such as SMILE laser eye surgery, implantable contact lenses (ICL), and advanced lens exchange can correct refractive errors permanently, freeing patients from glasses and contacts.

5. Why do some people call glasses a disability?

Because without them, many people cannot perform daily tasks safely or independently. Glasses are a widely accepted solution, but they remain an external aid; something modern surgery can now replace.